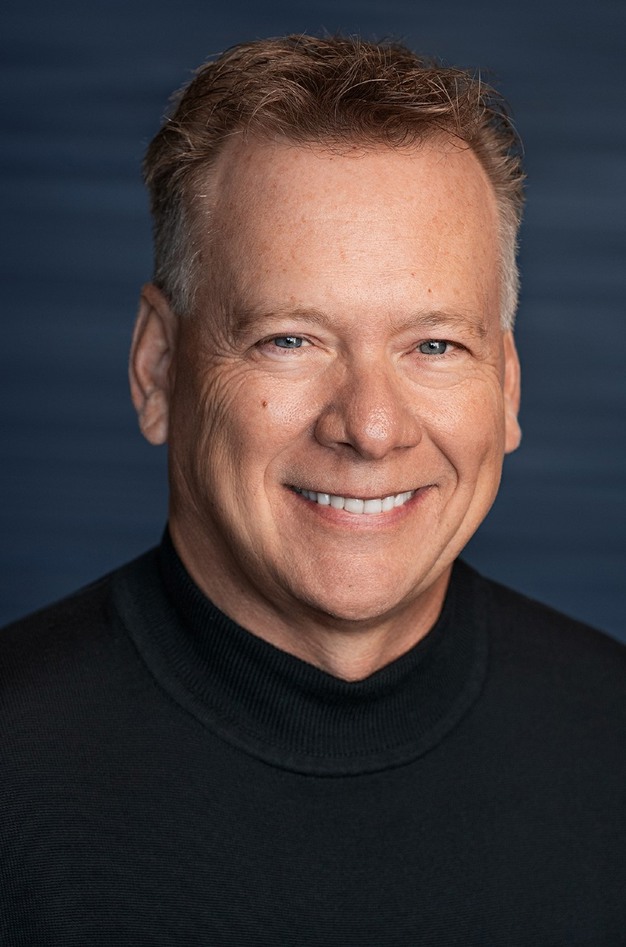

"In order to remain a leader in the vegetable industry, we have to get much bigger." Speaking is Michael DeGiglio, founder and CEO with Village Farms. Recently, the company announced a change in business structure, and an aggressive acquisition strategy. The decision—shaped by consolidation in North American retail, the capital to employ the use of emerging technologies to remain competitive in horticulture, and lessons learned from observing failed equity-backed ventures—has led to the formation of Vanguard, a new entity to house the company's produce operations.

© Village Farms

© Village Farms

Separate path

After nearly four decades of operating as a public greenhouse company, Village Farms has carved out a separate path for its fresh produce business. Vanguard, a joint venture backed by Kennedy Lewis Investment Management, Village Farms International, and Sweat Equities, will take over the U.S. greenhouse activities and all North American distribution center operations. The shift allows Village Farms International to retain full control of its Canadian greenhouse assets and operations, while giving the produce business access to long-term private capital partners and the flexibility to pursue aggressive M&A—planning an annualized revenue target to exceed one billion within the next three years.

© Village Farms

© Village Farms

"Could we, as Village Farms, become a top 10 company in produce in the United States? The answer was no. But through this joint venture, we believe we can become so," says Michael. Retail consolidation has only heightened the need for scale. "In the United States, eight retailers now control 80% of the market," Michael explains. "Scale is the key," agrees Charlie Sweat, founder of Sweat Equities and chairman of Vanguard's board of managers. "The goal is to have enough volume, quality, and diversity at a price that allows you to grow the relationships with the retailers as well as the foodservice players."

Right: Michael DeGiglio

Cost of being public

"In order to grow, we needed a lot of capital, and the right partner," Michael traces back. "We've been one of the few public greenhouse companies in the last twenty years, and the cost of being public is astronomical." He points out the shrinking number of listed companies on major U.S. exchanges, down from 12,000 to 4,000. "The produce industry is a low-margin, commoditized business," he adds. "There was no point anymore in being public."

Yet, he was adamant about protecting Village Farms' team. "I was 100% against selling to a competitor, because most of them would fire our people," he says. "All our people who have been with us for 20, 25, 30 years are all continuing." That continuity was a key requirement in structuring the joint venture.

© Village Farms

© Village Farms

Search for equity

Going private and looking for cash resulted in the search for an equity holder, but that's no easy route to take either. Over the last few years, it became clear that the returns in greenhouse cultivation do not align with the expectations of many private equity investors. "You have to work with someone who really understands produce. Farming is very different."

He cites their founding partner Kennedy Lewis's 20-year investment window, unusual in private equity, as key to the structure. "Most of these private equity guys have five-year investment horizons," Michael says. "Kennedy Lewis has $28 billion in long-term money. That was also very important."

Right: Charlie Sweat

From organic to everything

In addition to capital and a long-term vision, the new venture brings in leadership experience. Charlie Sweat with Sweat Equities joins the initiative with a focus beyond traditional greenhouse crops and a wealth of experience in running fresh produce organizations. In sixteen years, he increased the turnover of organic produce company Earthbound Farms from $10 million to $550 million before selling it to WhiteWave Foods in 2014.

The key is still producing good-tasting, healthy food at a price point that can be sustained through the supply chain to the consumer, he says.

"A lot of people thought CEA was kind of its own world, but it has to compete in the bigger shelf space and share of wallet with consumers. For us, the CEA world is a method of production, not a unique product segment. It's not about selling a tomato based on 95% less water usage, it still has to taste good and be at a price point that consumers will buy. You've got to win on the shelf and in taste. Historically, taste and quality declined as cost came down. In order to compete in the fresh produce chain, we need to eliminate costs without sacrificing flavor or nutrition."

That's where proprietary seeds and tech make a difference. "Another piece we're bringing into Vanguard is IP development, seed companies, new tech, that kind of innovation. We believe product development and strong IP around genetics and tech will play a big role in the bigger picture. It's how we keep the Vanguard network's offerings fresh, differentiated, and competitive on the shelf."

He adds the consumer's wallet has shrunken given the inflationary costs around the world in the last 36 months. "So consumers are having to make choices of how they spend their money and I think we've seen this across all categories. The higher cost items, even though they may be better for you, are a challenge for the mass buying population that is struggling with their disposable income around food."

"In other words, we want to drive supply chain efficiency to help our customers win. We can't do that without scale or new technologies. Vanguard will be profitable out of the gate, but with additional acquisitions, we will improve the margin profile and profitability of the business with size and volume."

While Charlie declined to disclose names of future targets, he confirmed that Vanguard is in active talks with companies across the fresh food value chain. The long-term goal is to create operating leverage and scale across a diverse portfolio of assets in North America. "The goal is to get to a multibillion-dollar revenue platform under Vanguard within the next 36 months."

Shareholder

Vanguard is not a rebranded part of Village Farms, but a newly created entity that will serve as a holding company for similar acquisitions. While Village Farms will remain a shareholder in Vanguard, holding approximately 40%, the produce business itself will operate independently. All of Village Farms' operational facilities in Texas now fall under Vanguard's management, although one greenhouse site is being leased from Village Farms.

Canadian vegetable greenhouses stay under Village Farms International's ownership, but their output will be marketed through Vanguard under the Village Fresh Greenhouse Grown name. Existing brands such as Village Farms Greenhouse Grown will continue under the Vanguard umbrella, and each acquired company in the future will also retain their operational independence under the holding company structure.

The name Vanguard, which will not serve as a brand name, was chosen with intent, Michael explains. "It means the forefront of any movement or activity," Michael explains. He acknowledges that other food companies use the name, but since it won't be consumer-facing, it serves as a strategic and internal brand identity. "Charge forward all the time and be the leader. That's why we chose that name."

CEO

Michael remains interim CEO of Vanguard for now, but a new CEO is expected to be appointed by year-end. He will continue to sit on Vanguard's five-member board, alongside Charlie Sweat, Village Farms CFO Steve Ruffini, a representative from Kennedy Lewis, and the future CEO.

"Each company we intend to buy will have their own CEO for that division," Michael notes, with shared services to be developed where synergies can be found, particularly in IT and HR.

© Village Farms

© Village Farms

For more information:

Sam Gibbons

Village Farms

Tel: +1 (407) 936 1190 © Village FarmsEmail: [email protected]

© Village FarmsEmail: [email protected]

www.villagefarms.com