Escalating tensions between Iran and Israel have reignited concerns about global energy and input flows through the Middle East, placing renewed geopolitical stress on one of the world's most critical shipping routes: the Strait of Hormuz. On June 22, Iran's parliament voted in favor of closing the strait following U.S. and Israeli military airstrikes. Although tensions appear to have temporarily eased, the situation remains volatile, and disruptions to petroleum and fertilizer shipments could resume with little warning.

While some U.S. agricultural products do move through the region, the Strait's broader importance to American agriculture stems from its role in setting global prices for fuel, fertilizer and freight. Even indirect impacts can pressure already-thin margins for farmers and ranchers. This Market Intel explores the role of the Strait of Hormuz in global trade, the relative importance of Middle East markets for U.S. agriculture, and how further escalation could increase input costs and market risk even further.

The Strait of Hormuz: A global chokepoint

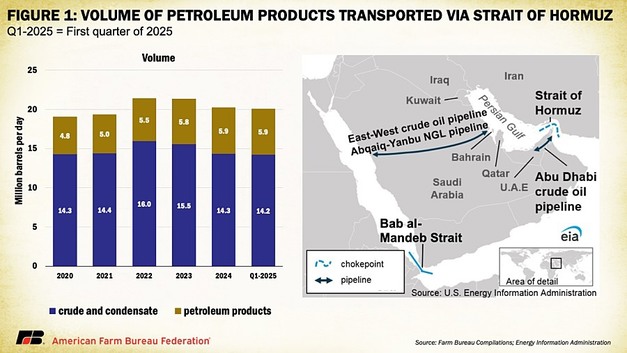

The Strait of Hormuz connects the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea and the broader Indian Ocean trade system. At just 21 miles wide, the strait carries an outsized share of global commerce. According to data compiled by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, roughly 14 million to 15 million barrels per day of petroleum, including crude oil, condensates (light liquid hydrocarbons) and refined products, passed through the strait in 2024. This accounted for over 20% of global petroleum consumption, underscoring its centrality in international energy markets.

© American Farm Bureau Federation

© American Farm Bureau Federation

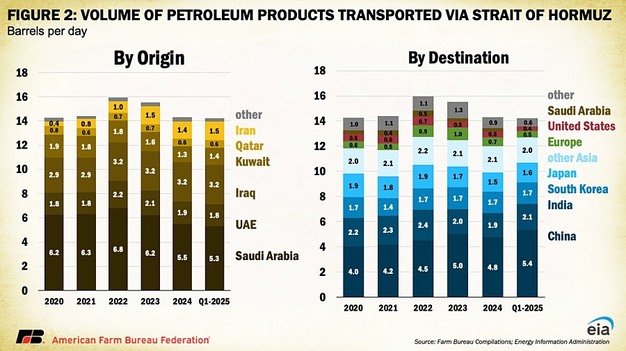

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq supply the bulk of petroleum volume moving through the Strait. More than two-thirds of the oil and gas flowing through the Strait is bound for Asia, with China, India, Japan and South Korea being top destinations. Any disruption to these flows reverberates globally, causing shipping delays, tightening supplies and pushing prices higher across fuel markets. For U.S. agriculture, this raises red flags, not because the U.S. depends on Middle East oil, but because oil is priced in global markets. Even indirect threats to Hormuz traffic introduce volatility into diesel, gasoline and fertilizer prices for U.S. farmers.

© American Farm Bureau Federation

© American Farm Bureau Federation

Agricultural producers are especially sensitive to fluctuations in energy markets. Diesel powers nearly every stage of crop production, including tillage, planting, spraying, harvesting and transportation. Natural gas, meanwhile, is as a critical feedstock in nitrogen fertilizer manufacturing. In 2025, U.S. farmers are projected to spend more than $22 billion on energy-related inputs, accounting for over 5% of total production expenses. Even modest increases in fuel prices can significantly alter breakeven margins and strain operational budgets.

During the most recent flare‑up between Israel and Iran in May and June 2025, benchmark Brent crude oil prices surged roughly 15‑20%, rising from around $65 in early June to approximately $78 per barrel amid fears of a blocked Strait of Hormuz before easing once a tentative ceasefire was announced. A comparable scenario unfolded in 2019, when attacks on tankers in the Gulf of Oman triggered a swift oil-market shock: Brent crude spiked nearly 20% at the open and settled about 10% higher by the close of trading that day. If shipping lanes through Hormuz are disrupted, global markets would be primed for similar price jolts.

Fertilizer flow at risk

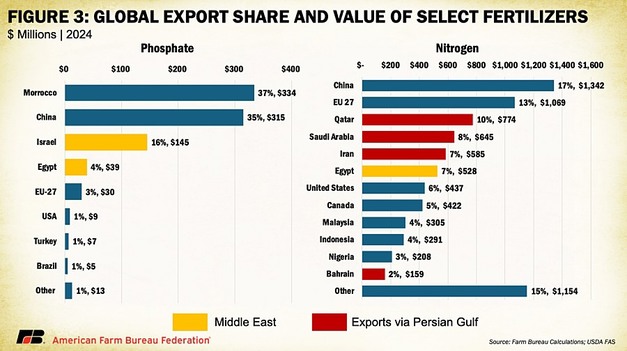

Though oil markets often dominate headlines during Middle East conflicts, the Strait of Hormuz is equally critical to the global fertilizer trade. In 2024, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Iran ranked as the third-, fourth-, and fifth-largest exporters of nitrogen fertilizer (primarily urea), together accounting for roughly 25% of global nitrogen exports. When Egypt and Bahrain are included, the broader region supplied more than one-third of total global nitrogen trade — valued at over $2.6 billion. Iran primarily ships fertilizer to Turkey and Brazil, two major agricultural producers that compete with the U.S. in global markets, raising the risk of downstream impacts on crop productivity and international price competitiveness.

Although phosphate exports are more geographically distributed, regional players like Israel and Egypt still contribute several hundred million dollars annually. With Israel directly involved in the current conflict and many shipments transiting through or near the vulnerable Strait, risks to phosphate supply chains remain elevated.

© American Farm Bureau Federation

© American Farm Bureau Federation

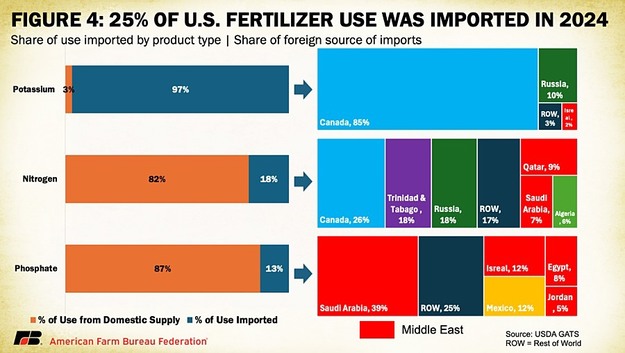

The United States remains exposed to global fertilizer markets. In 2024, the U.S. imported about 25% of its total fertilizer consumption, including 97% of its potash use, 18% of its nitrogen use and 13% of its phosphate use. While Saudi Arabia is not a top global exporter overall, it accounted for 39% of U.S. phosphate imports — highlighting a direct vulnerability tied to the region. Israel, Egypt, and Jordan supplied another 12%, 8%, and 5%, respectively, of U.S. phosphate imports. Qatar and Saudi Arabia also contributed 16% of U.S. urea (nitrogen) imports in 2024. Together, these trade relationships expose U.S. agriculture to regional instability in ways that can directly impact input availability and cost. With retailers currently offering summer fill programs, when fertilizer prices are typically lower due to reduced seasonal demand, geopolitical uncertainty could upend this window of opportunity and raise costs at a time when producers are looking to lock in savings.

© American Farm Bureau Federation

© American Farm Bureau Federation

Disruptions in Persian Gulf-origin supply often trigger global knock-on effects. When reliability in the region falters, major importers in Asia tend to shift demand toward alternative suppliers such as the U.S., Canada, or North Africa. This redirection strains global availability, increases competition and drives up prices — even in countries not directly dependent on the Gulf.

Fertilizer futures and retail markets are already factoring in supply risks. In early June, U.S. Gulf urea futures advanced approximately 7% over the previous month, while liquid nitrogen products like UAN-32 rose nearly 10% in May, mirroring the elevated pricing seen during past global disruptions. In 2022, for example, a convergence of global supply shocks, from Russia's invasion of Ukraine to natural gas constraints, drove nitrogen prices to historic highs. Fertilizer costs surged dramatically, with some nitrogen products rising over 155% compared to 2020 levels and potash increasing by more than 130%. These spikes had immediate influence on global planting decisions and production costs.

U.S. agricultural exposure to the Persian Gulf

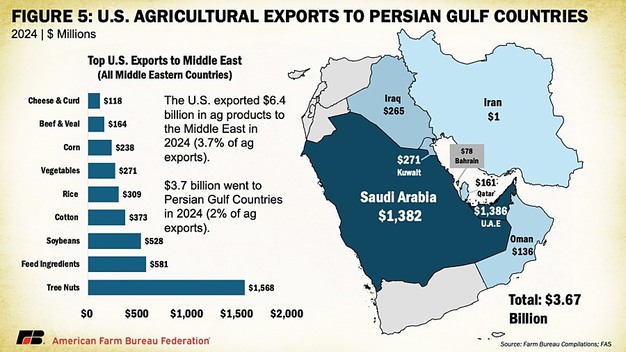

Although most attention has focused on input cost risks, ongoing instability in the region also raises questions about the reliability of U.S. agricultural trade with Persian Gulf countries. Relative to the Americas, Eastern Asia and Europe, the Persian Gulf represents a smaller, though still commercially relevant, destination for U.S. agricultural exports. In 2024, U.S. farmers and ranchers shipped approximately $3.7 billion in agricultural goods to countries along the Gulf, accounting for just 2% of total U.S. agricultural export value. The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia were the two largest buyers, each importing around $1.4 billion worth of American farm products. Iraq followed at $265 million, with smaller but consistent trade flows to Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain and Qatar.

While these markets are not central to U.S. export volumes, they are important for specific commodity sectors. High-value crops like tree nuts (including almonds, pistachios and walnuts) remain top exports to the broader Middle East, totaling more than $1.5 billion in 2024. U.S. producers also maintain a strong presence in the region for feed ingredients such as distillers grains and soybean meal, alongside marketable volumes of cotton, rice and dairy products.

© American Farm Bureau Federation

© American Farm Bureau Federation

Exporters serving these markets during periods of logistical volatility in the Strait of Hormuz or surrounding ports could face delays, elevated freight rates or additional insurance costs. While the Strait remains the region's most direct trade route, several Middle Eastern buyers maintain alternative logistics channels including overland transport through Saudi Arabia and Jordan, or maritime access via the Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb Strait that can help buffer against temporary disruptions in the Gulf. In a worst-case scenario, however, container shortages or risk premiums could reduce U.S. price competitiveness, prompting buyers to shift to alternative suppliers in the European Union, Australia or Central Asia. At present, most Gulf ports remain operational, and trade flows have not been significantly impacted by recent hostilities.

A global flashpoint with local implications

Ongoing tensions between Iran and Israel continue to fuel geopolitical uncertainty across the Middle East. For U.S. agriculture, the Strait of Hormuz functions less as a physical link and more as a global price lever for fuel, fertilizer and transportation.

Farmers and ranchers should not expect major export disruptions, but they should remain alert to the secondary effects of conflict: rising energy costs, shifting fertilizer markets and higher transportation insurance premiums. In a global system where pennies on the bushel can determine export success, even remote tensions can ripple into the realities at the American farm gate.

American Farm Bureau Federation

600 Maryland Ave SW

Suite 1000W

Washington DC 20024

Phone: (202)406-3600

www.fb.org